The Church has gradually gotten better at mental health stuff, but that doesn’t mean that you haven’t still absorbed a lot of unhealthy attitudes about anger from Church teachings.

In Part 1 of this series, we talked about anger, why it’s important, and how to manage it. In Part 2, we deconstructed some LDS teachings on anger. Today, we’ll talk about how LDS teachings about contention can prevent people from developing conflict-resolution skills and ultimately hurt relationships.

Disclaimer: I am a person with a blog, not a medical professional. This information is for educational purposes and is not a replacement for professional counseling.

Demonizing “Contention”

Exhibit A for teachings against contention: The Book of Mormon. At some point, you may have memorized 3 Nephi 11:29, which says:

For verily, verily I say unto you, he that hath the spirit of contention is not of me, but is of the devil, who is the father of contention, and he stirreth up the hearts of men to contend with anger, one with another.

The classical interpretation: All conflict is bad. Anger is bad. Don’t argue.

But conflict is inevitable because any two people will disagree at some point, probably on many points. Whether conflict is managed in a way that is constructive or destructive depends on the conflict-resolution skills of the people involved.

And when you have little to no experience with conflict, you can’t develop good conflict-resolution skills.

Seeing the Consequences

How do these teachings on contention often play out in relationships? Since we’ve been taught that contention and anger are bad, we (ex)Mormons often suppress our anger, consciously or unconsciously avoid discussion of our issues, and let our anger fester into resentment. When our anger and aggression has nowhere to go, we may become passive-aggressive. (Unsurprisingly, Mormons are notorious for passive-aggression.)

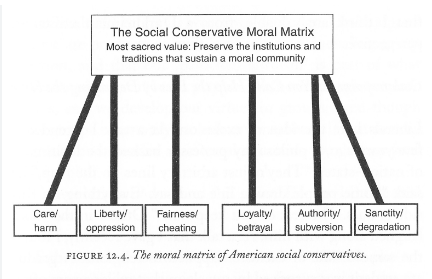

How do these teachings often play out within the structures of the Church? People who voice dissent are labeled as angry or even stirred up unto contention by Satan, and so the status quo continues, keeping the powers that be in control. Cue tone-policing of women, people of color, and LGBTQ+ people who try to explain how they’re being harmed.

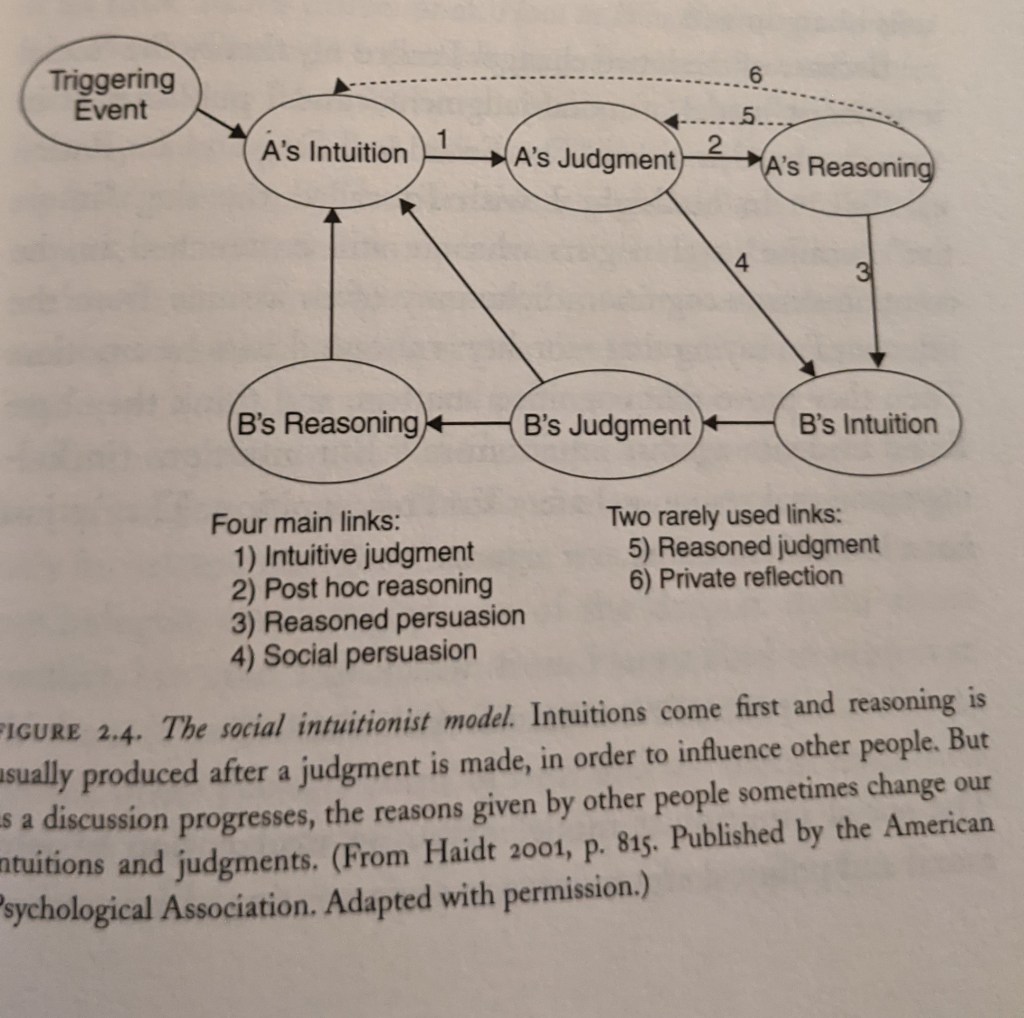

Often, the person bringing up the issues is calm and speaks with kindness, and yet, because the listener feels uncomfortable, they judge the dissident to be deceived by Satan.

An example where both the systemic and the personal consequences shine is in discussions among women in Relief Society. It’s very common for women to, in the course of commenting during Relief Society lessons, publicly drag their husbands for acting like children. (E.g., “Well, I have five children, if you count my husband, which I do [laughter], and I think . . . ) These women don’t feel allowed to or haven’t been successful in resolving their issues with the husbands themselves, who according to the Church are the patriarchal heads of the family, so complaining among other women is the outlet.

How can you unlearn passive-aggressive communication patterns? Learn conflict-resolution and communication skills. Sometimes we need conflict to move forward.

Differentiating Destructive Versus Constructive Conflict

I’d advise drawing a distinction between destructive and constructive conflict.

Destructive conflict is, well, destructive. It is disrespectful and makes your relationships worse.

One example of destructive conflict is yelling at people on social media to bring them around to your point of view (rude, accomplishes nothing). Another example is when one insults someone or targets their emotional weaknesses or sensitivities during an argument in order to gain the upper hand or make the other person feel bad.

In other words, destructive conflict involves being a jerk.

Constructive conflict, on the other hand, builds understanding and strengthens relationships. It may be uncomfortable in the moment but is necessary for you to move forward. Both parties come at the problem with a humble attitude and stay focused on the issue, without trying to “beat” the other person or make them feel bad. You’re trying to reach a solution together, not subdue the other person. You might need to point out patterns the other person engages in that upset you, but you should do this in a respectful way and be sensitive.

Teaching Kids About Conflict

My tip for mixed-faith families? Make the same distinction between types of conflict, but also use the Mormon terminology of “contention” to describe destructive conflict. That frees kids up to engage in constructive conflict.

For all kids, adults can model healthy conflict resolution and guide kids through their own conflicts when they’re young. Of course, if you don’t have these skills, then you’ll have to gain these yourself first. Counseling can be helpful for this. (Well-run group therapy can allow you to practice conflict-resolution skills with other participants before you try them in your everyday relationships under the guidance of a therapist, but these groups can be hard to find.)

One resource that’s helpful for explaining the concept of constructive conflict to kids is the Bluey episode called “Postman” (or, “Postman and Ground’s Lava”). In this episode, Bluey gets upset with her parents for having a friendly argument about whether the kitchen trash bin should be attached to the back of the cabinet door or not.

Bluey says that “people shouldn’t squabble” and commits to never squabbling again. She makes her dad write a love note to her mom to make up for the trash-bin squabble. Then Bluey tries to deliver the note to her mom while fulfilling an earlier promise to play Ground’s Lava with her sister, Bingo.

As they play, Bluey tries several techniques to prevent all squabbling. First, she tells Bingo that she has to agree with her, Bluey, always. Before long, Bingo decides this doesn’t work for her. Then, Bluey tries to always agree with Bingo, but that doesn’t work for Bluey. Then, they try to agree with each other. All options lead to squabbling.

Eventually, Bluey and Bingo have a squabble and work it out, and Bluey realizes that a squabble can resolve issues and make you feel good.

Avoiding Patriarchal Patterns

Did you notice that the immature “you need to always agree with me” approach that Bluey tries with Bingo is something the Church has relied on with women? I did.

In traditional LDS thought, you’re not supposed to have contention/conflict, including in a marriage. But disagreements are inevitable, and the solution the patriarchy has decreed is that the woman needs to obey (or “hearken to”) the man (unless he wants something contrary to God’s commandments).

Fortunately, many LDS couples ignore that temple covenant and learn communication skills, but in many marriages, the woman repeatedly has to swallow her truth and inevitably becomes resentful.

Note that if a person has very little power, then they’re more likely to have to resort to passive-aggression or manipulation to get their needs met. Misogyny often claims these are natural female behaviors, but please note that they are survival strategies developed in response to patriarchy.

If you have learned these strategies, you can unlearn them and replace them with boundaries and conflict resolution.

Don’t continue this patriarchal pattern post-Mormonism! It’s a recipe for resentment and bad marriages.

Instead, learn how to communicate effectively and build conflict-resolution skills.

You must be logged in to post a comment.